Learn the musical alphabet with this free bass lesson from Lutz Academy! With this method, you’ll be able to easily apply it to the fretboard and make sense of it on bass.

The 12 Notes

The musical alphabet is made up of twelve notes:

A – A# – B-C- C# – D – D# – E-F – F# – G – G#

These twelve notes repeat over and over again.

Natural Notes

There are seven natural notes: A – B – C – D – E – F – G.

Flat Notes (b)

When you add a flat (“b” symbol) to a natural note, you lower it’s pitch by one half step. For example, when you flat a C natural note, it becomes “Cb” which will be lower in pitch than C.

Sharp Notes (#)

Sharping a note is the opposite of flatting it. A sharp symbol (“#”) raises the note by one half step. So, when you sharp a C natural note, you get C#, which will be higher in pitch than C.

The Complete Alphabet

We use both sharps and flats in music as they both have their purpose. When written out using both sharps and flats, the musical alphabet appears like this:

A – A#/Bb – B-C – C#/Db – D – D#/Eb – E-F – F#/Gb – G – G#/Ab

The notes with the “/” in between them are called “enharmonic equivalents”.

Enharmonic Equivalents

Enharmonic equivalents is a fancy name for two notes that sound alike. A# and Bb sound the same because they are the same on bass. We play them the same way, but we have two ways of writing this note for theory purposes.

When you get to the point of using scales and keys, you’ll find yourself using both sharps and flats. While you could use just one or the other since enharmonic notes are the same, you should really employ both sharp and flat notes in order for whatever you write to make sense musically.

Sharp or Flat?

When you write music, you might find yourself wondering when to use a sharp note and when to use a flat note. Let’s use a quick example (it’s okay if you don’t grasp the theory yet, you’ll get it with time!):

Ab Major Scale

The notes of the Ab Major Scale:

A♭, B♭, C, D♭, E♭, F, G

We need to have one “form” of each note. Remember there are only seven letters in the musical alphabet:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G

But A, C, D, F, and G each have another form: sharp/flat, making for twelve notes total (we’ll explain in a minute why there is no B#/Cb or E#/Fb).

Every scale/key has seven notes. Here’s the rule: you cannot use the same letter twice! That’s why we need to have both sharp and flat notes, or enharmonic equivalents. Here’s a look at what we should not do:

A♭, B♭, C, C#, E♭, F, G

See what happens when we write Db as C#? We have no form of D at all, and we end up with two forms of C (C and C#). While this version of the scale will be played the same, on paper and in theory, it’s wrong!

Half Steps & Whole Steps

We measure the distance between notes with “steps”. In the musical alphabet, every natural note is one whole step apart, except for the notes B + C and E + F. These notes are only one half step apart, which is why there is no B#/Cb or E#/Fb (although, they do exist, but we’ll get into microtonal music later…).

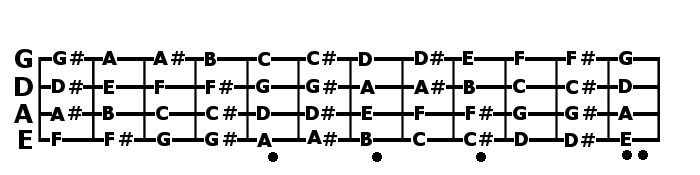

On bass, each fret is one half step apart. So from the open string note, the 1st fret is one half step higher, and so on.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Recap

A lot to take in? Of course! Here’s a recap:

- There are seven natural notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, G.

- Every scale is made up of seven notes, but we need one form of each letter to have a theoretically complete scale, which is why we use both flat and sharp notes.

- There is no B#/Cb or E#/FB in our alphabet, because these notes are only a half step apart while all other natural notes are a whole step apart.

- Written out completely with enharmonic equivalents (notes that sound the same), the alphabet is:

A – A#/Bb – B-C – C#/Db – D – D#/Eb – E-F – F#/Gb – G – G#/Ab

The post Learn the Musical Alphabet – Bass Lesson appeared first on Lutz Academy.